February 2021 saw extremely cold and snow conditions over northern Europe, associated with upsets to the polar vortex. But what happened afterwards, as winter transitioned to spring?

The snow storms and cold weather that prevailed over northern Europe in February this year were consistent with disruptions to the normal prevailing westerly (i.e. air originating from the west) airflow that arise from what have become to be known as ‘Beast From the East’ type events in the United Kingdom.

These events, as the name suggests, are characterised by prevailing easterly winds, subjecting the UK to cold, Siberian – or Baltic – originating air that picks up moisture over the North Sea and then blankets the country in snow. ‘Beast’ events are distinguisehd from normal snowly ‘blips’ that we might get as normal westerly storms systems pass over the UK (these will often give 24 hours worth of northerly or easterly winds as the wind direction backs around the low pressure storm). Rather, ‘Beast’ events sit in for a few days.

In December 2020 and January 2021 the UK media went haywire, since the pre-cursor signal to surface ‘Beasts’ had been detected in the upper atmoshpere and leaading researchers operating in the field were quick to raise the alarm. With good reason as it transipired. But let’s look back, now that the snow dust has settled! Is the Polar Vortex still there? Why aren’t we hearing about it now?

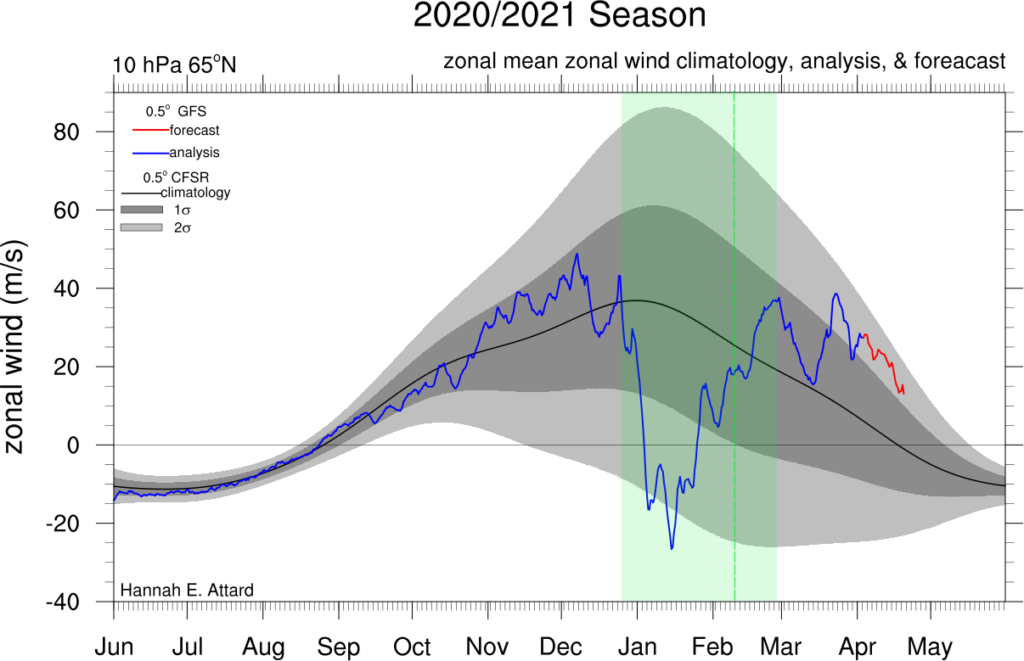

To help with our take, Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University Assistant Professor Dr. Hannah Attard keeps a an extremely informative rolling overview of upper-air conditions for the current season, which she’s kindly allowed us to reproduced here. We’ve annotated some labels of our own in green. The blue line in her plot shows the upper air wind direction in the Northern Hemisphere since June 2020, with some forecast data at the end of the series in red. Values <0 means the wind direction in the high atmosphere have reversed — the ‘alarm’ for a possible Beast event, whilst the solid black line is what ought to happen if the year was exactly normal (i.e. the black line is a climatology derived from a historical record, all averaged together).

Check out the dip in the lead up to Christmas 2020. This was the initial signal that piqued researchers’ (and later the media’s) interest that something was afoot. In fact the eventual wind reversal peaked around January 15th — and the magnitude of the reversal was such that it went beyond recently-observed events in other years (represented by by the grey shading).

The abrupt dip was the alarm for possible cold surface weather and we’ve marked on the approximate date of the main snow episodes over the UK with the vertical green line around February 10th (ish). Interestingly, the period of the delay between the upper air ‘alarm’ and the eventual materialisation of surface disruptions this year was pretty bang on for a Beast event — should they indeed get to the land surface at all. (about 1/3 appear to make it to the surface, from the high atmosphere).

In any event, the weather got cold — very snowy in parts of northern Europe and then, of course, the snow melted. High aloft, though, we can see that virtually at the same time the surface of the atmosphere was being disrupted, the upper air conditions had pretty much returned to normal: i.e. whilst we, at the surface, were living the anomaly, the high atmosphere wasn’t really that unusual and unusual conditions had receded there.

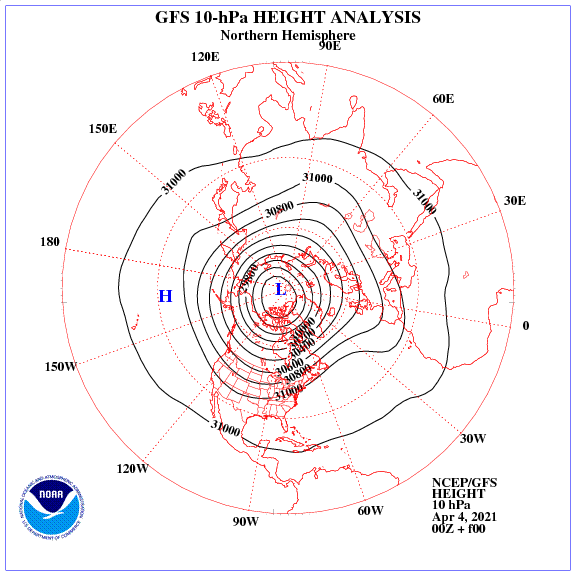

So what has happened since February 2021? Well, the Polar Vortex reformed in to a stable circular airmass, and has sat nicely over the pole. It’s still there — check out this plot for upper air data, 4th April 2021:

Meteorological spring has sprung and Europe has seen some really warm conditions for an intermittent few days at least. As the sun re-appears over polar regions, similarly the dynamics of the upper atmosphere re-oraganises after the long polar winter; eventually the north-south thermal gradient, so strong during the winter darkness, is no longer sufficient to support such a defined circular structure to the winds, and the circulation pattern naturally deforms into a more ‘wavey’ pattern associated with spring. You can see the usual date (in a typical year) when this might happen in Hannah’s plot — somewhere around mid April as the black line crosses the zero value.

So there you go, the Polar Vortex is still there. For now at least. But is slowly giving up its influence for another year and letting in the sharp changes of weather that have you reaching for your t-shirt one day and your woolly hat the next. Happy Easter! – Dr. Craig Wallace